Research conducted by Dr. Yuchen Tan and colleagues has revealed that the ancient settlement of Jiahu, located in the North China Plain, not only survived the abrupt climatic event known as the 8.2 ka event but displayed remarkable resilience and social transformation. This finding challenges the prevailing notion that the event was universally catastrophic for all populations in the region. The research is detailed in the journal Quaternary Environments and Humans.

The 8.2 ka event was a significant climate phenomenon that occurred during the Holocene, marked by rapid cooling and drying across the Northern Hemisphere. Triggered by the collapse of the Laurentide ice sheet in North America, this event disrupted the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation and shifted the Intertropical Convergence Zone southward, which affected the East Asian Summer Monsoon. As a result, regions dependent on this weather system, including the North China Plain, faced severe cooling and drought conditions.

Situated in Henan Province and occupied from approximately 9,500 to 7,500 years ago, Jiahu was characterized by a network of rivers and channels that supported early human settlement. While many nearby sites experienced significant disruption or complete abandonment during the 8.2 ka event, Jiahu exhibited notable resilience. To investigate this, the researchers applied resilience theory alongside the Baseline Resilience Indicator for Communities (BRIC) model to analyze how Jiahu adapted during this climatic upheaval.

Originally developed in the field of ecology, resilience theory aims to explain how ecosystems respond to disturbances. While it has faced criticism for its lack of clarity, Dr. Tan and their team adapted the BRIC model, traditionally used to assess modern communities’ responses to natural disasters, to evaluate ancient societies’ reactions to environmental changes. Dr. Tan noted, “Our aim in adapting BRIC was to provide a transferable framework for examining how human systems reorganize in response to abrupt climatic or environmental change across a wider range of sites.”

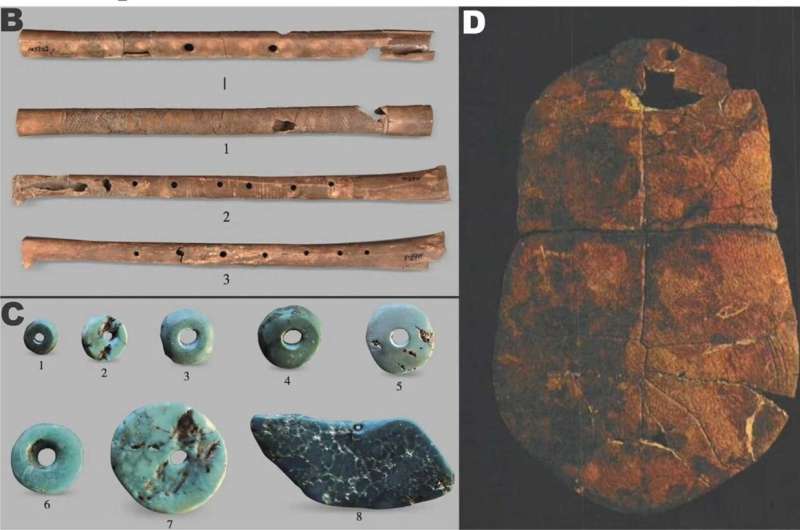

The researchers assessed archaeological evidence from three distinct phases of Jiahu’s occupation: Phase I (9,000–8,500 years ago), Phase II (8,500–8,000 years ago), and Phase III (8,000–7,500 years ago). Notably, Phase II coincided with the 8.2 ka event and revealed significant social transformations. The number of burials surged from 88 in Phase I to 206 in Phase II, reflecting both increased mortality and an influx of immigrants from surrounding areas. Additionally, burial practices became more standardized, and the presence of grave goods increased, suggesting emerging wealth disparities and social stratification.

Analysis of skeletal remains indicated a greater division of labor, with males showing higher rates of osteoarthritis, likely due to increased physical exertion in securing resources. This influx of migrants and the reorganization of labor may have enhanced Jiahu’s ability to adapt and thrive amidst the challenges posed by the 8.2 ka event.

By Phase III, after the climatic event had passed, the number of burials decreased to 182, and grave goods became less common. This change suggests that Jiahu actively reorganized and innovated in response to the climatic crisis. According to Dr. Tan, the ultimate collapse of the settlement occurred later, following Phase III, due to frequent climatic fluctuations that triggered flooding, rendering the settlement unviable.

This study highlights the adaptability of ancient communities in the face of environmental crises and demonstrates the applicability of the BRIC model to archaeological contexts. The findings from Jiahu offer valuable insights into how human societies can reorganize and respond to abrupt climatic shifts, challenging the notion that all populations react uniformly to such events.