Research from Cornell University has revealed significant insights into how soil microbes affect carbon storage, a key factor in combating climate change. Published in Nature Communications on December 10, 2023, the study demonstrates that soil molecular diversity increases as microbes break down dead plant material, with notable implications for carbon sequestration.

Soils globally contain three times more carbon than the atmosphere and all plants combined. Understanding the role of soil microbes in recycling organic materials is crucial, as some processes release carbon dioxide (CO2) back into the atmosphere, while others mineralize it for long-term storage. The research focuses on how the molecular diversity in soils changes during the decomposition of plant litter.

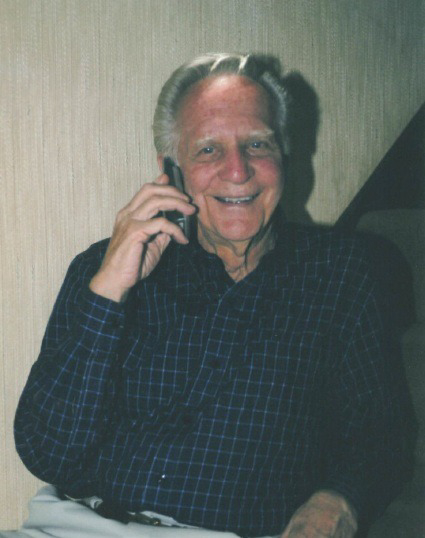

Johannes Lehmann, a professor of soil and crop sciences at Cornell and the paper’s senior author, emphasized the importance of this research. “This is a hugely important question: can we lose less carbon from soil, or can we even increase our soil carbon stocks?” he stated. The findings indicate that even small changes in soil carbon can have significant effects on atmospheric CO2 levels, which is vital for climate regulation.

The study, led by Rachelle Davenport, Ph.D. ’24, identified a peak in molecular diversity 32 days after the initiation of microbial decomposition. Initially, diversity increased, but it began to plateau and subsequently decline. This trend offers empirical evidence supporting the theory that higher molecular diversity may inhibit rapid decomposition, allowing for greater carbon retention in soils.

For decades, the scientific community has operated under the premise that soil organic carbon accumulation stemmed primarily from resistant plant materials. However, a landmark paper co-authored by Lehmann in 2011 challenged this view, positing that soil organic carbon results from complex interactions involving soil microorganisms and minerals. This recent study builds on that foundation, presenting new methodologies and findings.

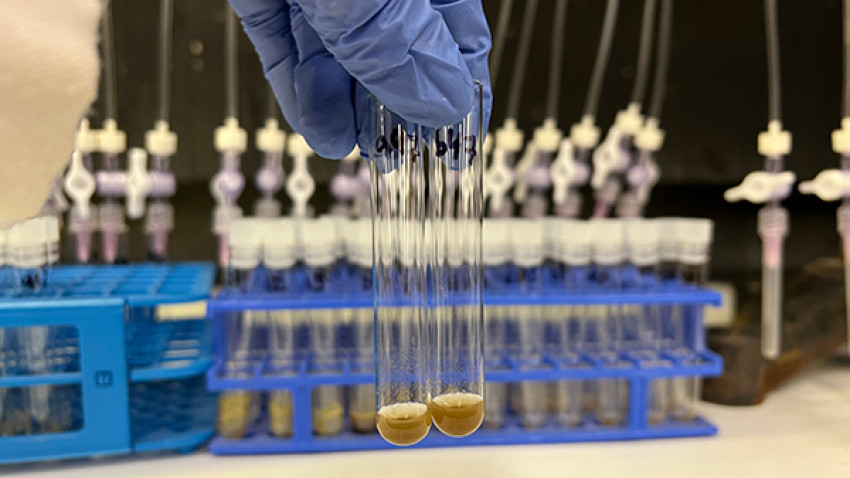

Researchers employed innovative techniques to measure molecular diversity, extracting organic matter with water and analyzing it using high-resolution mass spectrometry. Notably, the study is the first to utilize 18O heavy water—water tagged with the oxygen-18 isotope—to trace changes in soil molecular composition due to microbial activity. This contrasts with traditional methods, which often rely on glucose, potentially skewing results regarding microbial behavior.

Davenport highlighted the significance of this approach, stating, “When you trace activity via carbon, you usually feed microbes glucose…this affects their metabolism and then you’re not really accurately measuring microbial activity.” The collaboration with the Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory in Richland, Washington, proved essential in developing this new method.

The work involved contributions from 11 co-authors across seven institutions in six U.S. states and the Netherlands, supported by multiple grants, including the Schmittau-Novak Small Grant and a Graduate Research Grant from the Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability. Davenport’s research also benefited from a grant she received in 2022, enabling her to mentor an undergraduate researcher, Caleb Levitt, who played a critical role in measuring soil carbon dioxide emissions.

Looking ahead, the researchers aim to explore how increased diversity among soil molecules, microorganisms, and minerals can enhance carbon storage in soils. If successful, these findings could inform improved farming and forest management practices that bolster soil health and contribute to climate change mitigation.

In summary, the study underscores the vital role of soil microbial communities in carbon dynamics, providing a clearer understanding of how to manage these ecosystems for climate resilience. As Lehmann noted, “We still have much to learn, but this is one important piece of the bigger puzzle.”