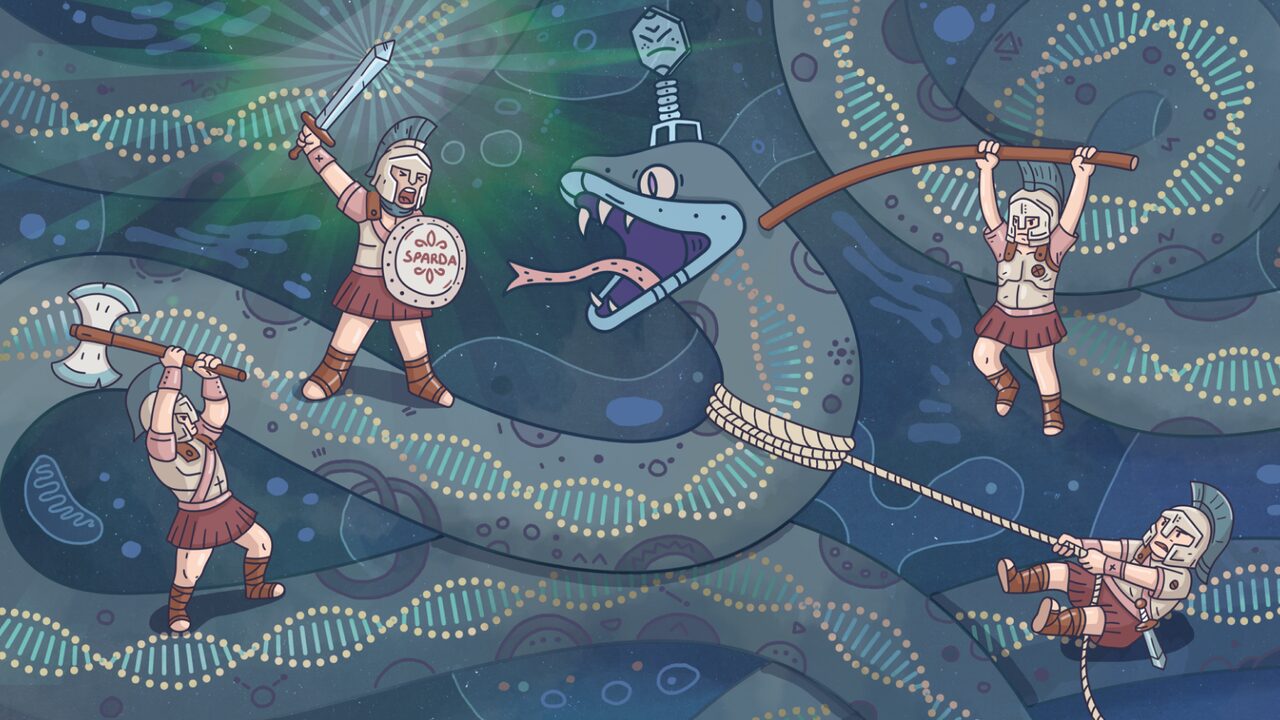

Recent research has unveiled a bacterial defense system known as SPARDA (short prokaryotic Argonaute, DNase associated), potentially paving the way for innovative biotechnological applications. This discovery, highlighted in a study published in the journal Cell Research, showcases how SPARDA could enhance diagnostic tools currently utilizing the popular gene-editing technology, CRISPR.

CRISPR has transformed genetic research by simplifying gene editing. Originally an immune defense mechanism in bacteria, CRISPR has been adapted for human use. The study led by biochemist Mindaugas Zaremba from Vilnius University explores SPARDA, a system that researchers previously studied only in limited capacity. Zaremba and his colleagues have demonstrated that SPARDA employs a “kamikaze-like” approach to protect bacteria from foreign DNA, including plasmids and phages.

When faced with an external threat, SPARDA’s proteins degrade the DNA of both the invading pathogens and the infected bacterial cells. As Zaremba explained, this mechanism effectively halts the spread of infection within bacterial populations, albeit at the cost of the host cell’s survival.

Uncovering SPARDA’s Mechanism

The molecular function of SPARDA had remained elusive until Zaremba’s team utilized the AI protein analysis tool, AlphaFold. This innovative tool predicts the three-dimensional structure of proteins based on their amino acid sequences. The study focused on SPARDA systems extracted from two different bacteria: Xanthobacter autotrophicus, a soil microbe, and Enhydrobacter aerosaccus, found in Michigan’s Wintergreen Lake.

In their analysis, the team transferred SPARDA systems into the model organism E. coli. They discovered that each argonaute protein within the SPARDA system contained a crucial “activating region,” termed the beta-relay. This region resembles electrical relay switches, which toggle between “on” and “off” states. When the proteins detect foreign DNA, these switches undergo a shape change, allowing the proteins to form complexes with other activated argonautes.

These complexes align to form chains that effectively chop up surrounding DNA, sacrificing the host to prevent further infection. Zaremba’s findings suggest that the beta-relay may be a universal feature among similar proteins, enhancing our understanding of bacterial defense mechanisms.

Potential Applications in Diagnostics

Zaremba posits that SPARDA’s precise recognition system for foreign DNA could be harnessed for human applications. The system’s activation serves as a last-resort measure for bacterial cells, indicating an advanced capability for identifying and responding to genuine infections. Researchers could modify the beta-relay to activate only upon recognizing specific genetic sequences, such as those associated with flu viruses or SARS-CoV-2.

This capability could significantly improve existing CRISPR-based diagnostic tools, which currently face limitations. CRISPR diagnostics rely on specific DNA sequences, known as PAM sequences, to function effectively. These sequences must match precisely for the system to operate, akin to a plug fitting into a socket. In contrast, Zaremba’s research indicates that SPARDA systems do not require such PAM sequences, offering a more adaptable solution for DNA diagnostics.

The implications of this research extend beyond theoretical applications. The ability to detect a wider range of pathogens could enhance the effectiveness of diagnostic tests, ultimately benefiting public health. As SPARDA research progresses, it holds the promise of revealing further insights into the relationship between bacterial systems and genetic engineering.

While SPARDA is still in the early stages of research, its potential as a biotechnology tool is being recognized. As scientists continue to explore its intricacies, the findings may contribute to addressing significant challenges in genetics and beyond.