Radio astronomy faces challenges from an unexpected source: satellites that orbit thousands of kilometers above Earth. A recent study conducted by a team from the CSIRO (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation) has assessed whether geostationary satellites, positioned at an altitude of 36,000 kilometers, emit radio frequencies that could interfere with astronomical observations. The findings indicate that these satellites largely maintain a low profile in the radio spectrum.

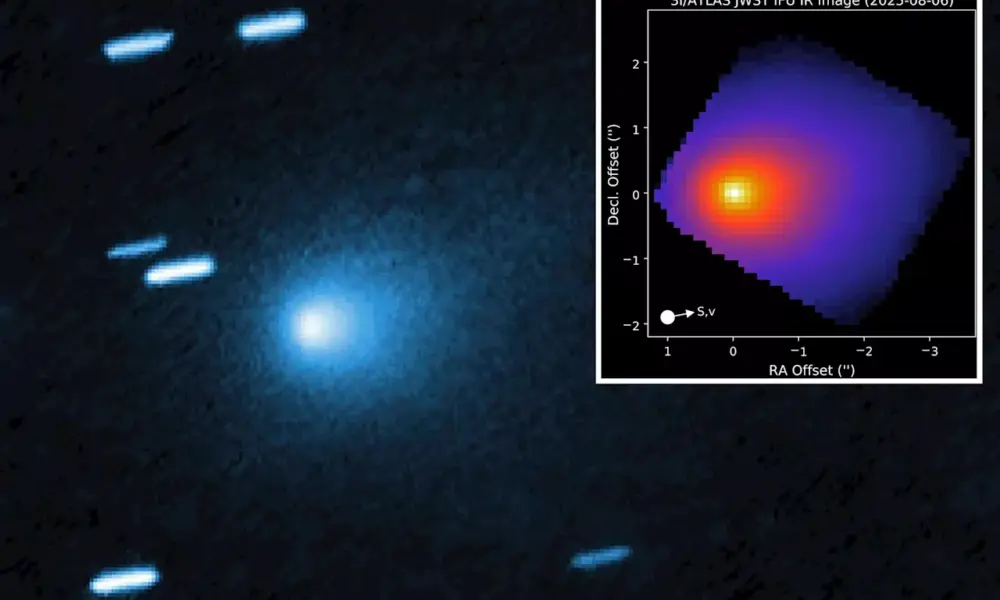

The research team utilized archival data from the GLEAM-X survey, collected by the Murchison Widefield Array in Australia in 2020. This survey focused on frequencies ranging from 72 to 231 megahertz, which are critical for the operation of the upcoming Square Kilometer Array (SKA). By tracking up to 162 geostationary and geosynchronous satellites over a single night, the researchers employed a technique that stacked images at each satellite’s predicted position to detect any unintended radio emissions.

The results were promising. The majority of the observed satellites did not emit detectable signals in the frequency range critical to astronomers. The team established upper limits for emissions from these satellites at better than 1 milliwatt of equivalent isotropic radiated power within a 30.72 megahertz bandwidth. Notably, the best limits reached a remarkable 0.3 milliwatts. Only one satellite, Intelsat 10–02, demonstrated a possible emission at around 0.8 milliwatts, which still falls well below the significant emissions observed from low Earth orbit satellites that can radiate hundreds of times more powerfully.

The significance of these findings lies in the distance and geometry of geostationary satellites. Positioned at ten times the distance of the International Space Station, any radio emissions from these satellites dissipate considerably by the time they reach ground-based telescopes. Additionally, the study’s observation strategy, which focused on areas near the celestial equator, allowed each satellite to remain within the telescope’s wide field of view for extended periods. This approach facilitated the detection of even intermittent emissions through sensitive stacking techniques.

Looking ahead, the Square Kilometer Array, once operational, will vastly surpass current instruments in sensitivity within the low-frequency spectrum. What may seem like harmless background noise to today’s telescopes could pose significant interference for the SKA. These measurements provide essential baseline data, aiding in the prediction and mitigation of future radio frequency interference.

As satellite constellations expand and radio telescopes become increasingly sensitive, the pristine radio quiet that astronomers have relied upon for decades is becoming endangered. Even satellites designed to operate within specific protected frequencies can unintentionally leak emissions through their electrical systems, solar panels, or onboard computers.

Currently, geostationary satellites appear to be responsible tenants in the low-frequency radio spectrum. However, whether they will continue to be respectful as technology advances and traffic in orbit increases remains uncertain. The ongoing evolution of space technology necessitates vigilance to ensure the integrity of astronomical research.

For more detailed findings, the research paper titled “Limits on Unintended Radio Emission from Geostationary and Geosynchronous Satellites in the SKA-Low Frequency Range” is available on the arXiv preprint server, published on December 15, 2025.