Recent research has revealed that cosmic rays produced by nearby supernovae could play a significant role in the formation of Earth-like planets. This finding, published in the journal Science Advances on December 21, 2025, challenges long-held theories about the origins of rocky planets in our solar system.

For decades, scientists believed that short-lived radioactive elements, such as aluminum-26, were essential for the formation of Earth. These elements were thought to have been introduced into the early solar system by a supernova explosion. Such elements helped heat young planetesimals, leading to the loss of volatile materials and water during their formation. However, this classic “injection” scenario implied a highly improbable series of events, requiring a supernova to explode at just the right distance to deliver radioactive material without destroying the fragile protoplanetary disk.

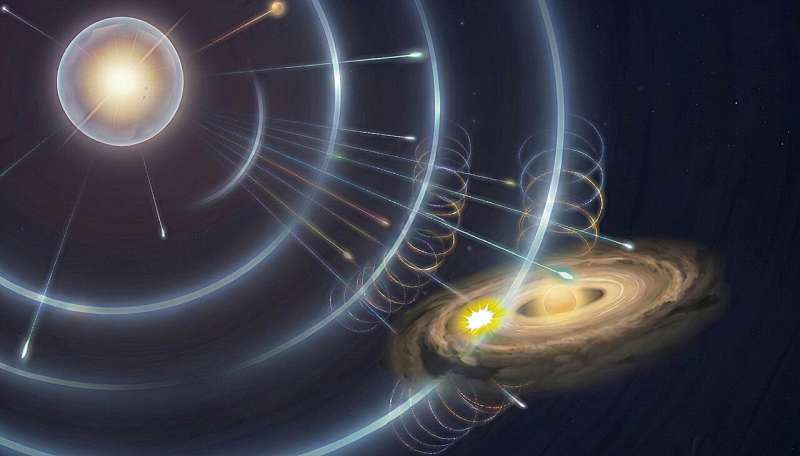

Ryo Sawada, a researcher at the Institute for Cosmic Ray Research at the University of Tokyo, questioned the adequacy of this explanation. As supernovae are powerful cosmic events that also act as particle accelerators, Sawada proposed an alternative scenario: what if the young solar system was not just impacted by supernova debris but was also surrounded by a pervasive cloud of cosmic rays?

In their study, Sawada and his colleagues conducted numerical simulations to explore the effects of cosmic-ray acceleration and nuclear reactions. They discovered that when cosmic rays interact with the protosolar disk, they can induce nuclear reactions that create short-lived radioactive elements, including aluminum-26. Remarkably, this mechanism can produce the necessary amounts of these elements at a distance of about one parsec from a supernova—an entirely typical distance within star clusters.

This revelation suggests that the conditions required for Earth-like planets could be more common than previously thought. Instead of relying on a rare supernova event, the young solar system may have simply existed within a stellar nursery that included massive stars, which eventually exploded.

The implications of this research extend beyond just the formation of Earth. If cosmic-ray baths are indeed common in environments where sun-like stars form, then the processes that shaped Earth could also be present around a substantial number of other stars. This insight raises the possibility that water-depleted rocky planets might not be as rare as previously believed.

While the study does not claim that every habitable planet can be traced back to a supernova, it does indicate that the formation of Earth-like planets may not hinge on a miraculous event. Various factors, such as the lifetime of the protoplanetary disk and the structure of star clusters, still play significant roles in planetary formation.

Sawada emphasizes the interconnectedness of astrophysical processes and how insights from high-energy astrophysics can illuminate questions in planetary science. By recognizing the importance of cosmic-ray acceleration, researchers may gain a clearer understanding of the origins of Earth-like planets and the conditions that foster habitability.

This research not only provides a fresh perspective on the formation of rocky planets but also highlights the complexity and beauty of the cosmos. As scientists continue to explore these connections, the story of how Earth came to be may become even more fascinating.