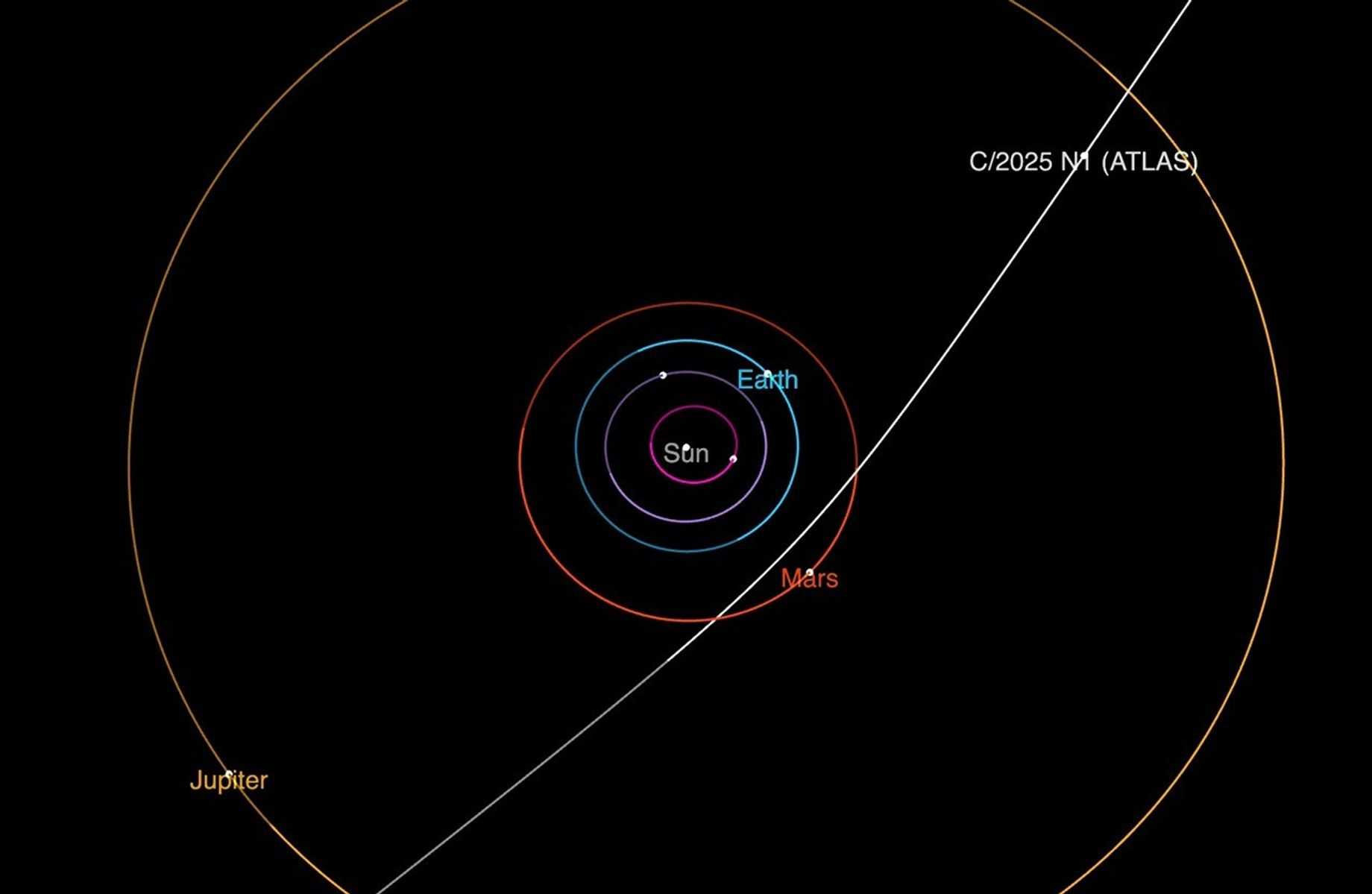

An interstellar comet named 3I/ATLAS has recently completed its closest approach to the Sun, positioning itself on an outbound trajectory. This remarkable object, which originated beyond our solar system, came within approximately 126 million miles (about 203 million kilometers) of our star. Ground-based telescopes currently cannot observe it, as it is located behind the Sun, but astronomers anticipate renewed visibility in the coming weeks, according to Darryl Seligman, an assistant professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at Michigan State University.

Stargazers should be able to catch a glimpse of 3I/ATLAS in the predawn sky starting from November 11, as astronomers are keen to maximize their observations before the comet exits our solar system. Its closest approach to Earth will occur on December 19, at a distance of about 168 million miles (or 270 million kilometers), though it poses no threat to our planet, according to the European Space Agency.

Understanding the Interstellar Visitor

This comet, only the third known interstellar object to traverse our solar system, has been under scrutiny since its discovery on July 1. Each observation provides critical insights into its composition, potentially revealing differences from comets that formed in our own solar system. Comets are often described as “dirty snowballs,” with a nucleus made of ice, dust, and rock. As they approach stars like the Sun, the heat causes them to emit gas and dust, forming their characteristic tails.

Astronomers are eager to gather as much data as possible, particularly as 3I/ATLAS nears the Sun. The release of material during this close encounter could offer invaluable information about its origins. “When it gets closest to the sun, you get the most holistic view of the nucleus possible,” Seligman explained. “One of the main things driving most cometary scientists is, what is the composition of the volatiles? It shows you the initial primordial material that it formed from.”

Powerful instruments, including the Hubble Space Telescope and the James Webb Space Telescope, alongside various missions like SPHEREx, have been employed to study the comet. The observations have detected compounds such as carbon dioxide, water, carbon monoxide, and carbonyl sulfide emanating from the comet as it moves closer to the Sun. Preliminary studies suggest that 3I/ATLAS may be between 3 billion to 11 billion years old, shedding light on the ancient materials that predate our solar system, which formed around 4.6 billion years ago.

Future Observations and Challenges

While 3I/ATLAS faded from the view of ground-based telescopes in October, it remained observable to other missions, including PUNCH (Polarimeter to Unify the Corona and Heliosphere) and SOHO (Solar and Heliospheric Observatory). The comet made its closest approach to Mars on October 3, coming within 18.6 million miles (around 30 million kilometers) of the planet, where orbiting spacecraft captured images of it.

Despite a government shutdown hindering data sharing from NASA missions observing the comet since October 1, the European Space Agency’s Mars Express and ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter managed to capture some views of 3I/ATLAS. The observations were challenging, as noted by Nick Thomas, principal investigator of the ExoMars camera, who described the comet as being 10,000 to 100,000 times fainter than the typical targets.

Looking ahead, ESA’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer, or Juice, is set to attempt observations of 3I/ATLAS in November, utilizing multiple instruments despite the increased distance from the comet compared to earlier observations. However, data from these observations is not expected to be available until February due to the spacecraft’s data transmission rate.

As scientists continue to monitor 3I/ATLAS, they express optimism regarding the potential discoveries that lie ahead. “We’ve got several more months to observe it,” Seligman stated. “And there’s going to be amazing science that comes out.”