The field of astronomy reached a pivotal moment on November 1, 1995, when Swiss astronomers Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz announced the discovery of a Jupiter-sized planet orbiting a sunlike star, known as 51 Pegasi b. This groundbreaking find at the Haute-Provence Observatory in France marked the beginning of a new era in the search for extraterrestrial life and the study of exoplanets.

In September 1994, Mayor and Queloz embarked on a mission to locate a planet around a sunlike star located approximately 50 light-years from Earth. After nearly 18 months of meticulous observations, they identified significant anomalies in the trajectories of various stars. Their focus ultimately narrowed to 51 Pegasi, a middle-aged star in the constellation Pegasus that exhibited a noticeable wobble, suggesting gravitational influence from an orbiting planet.

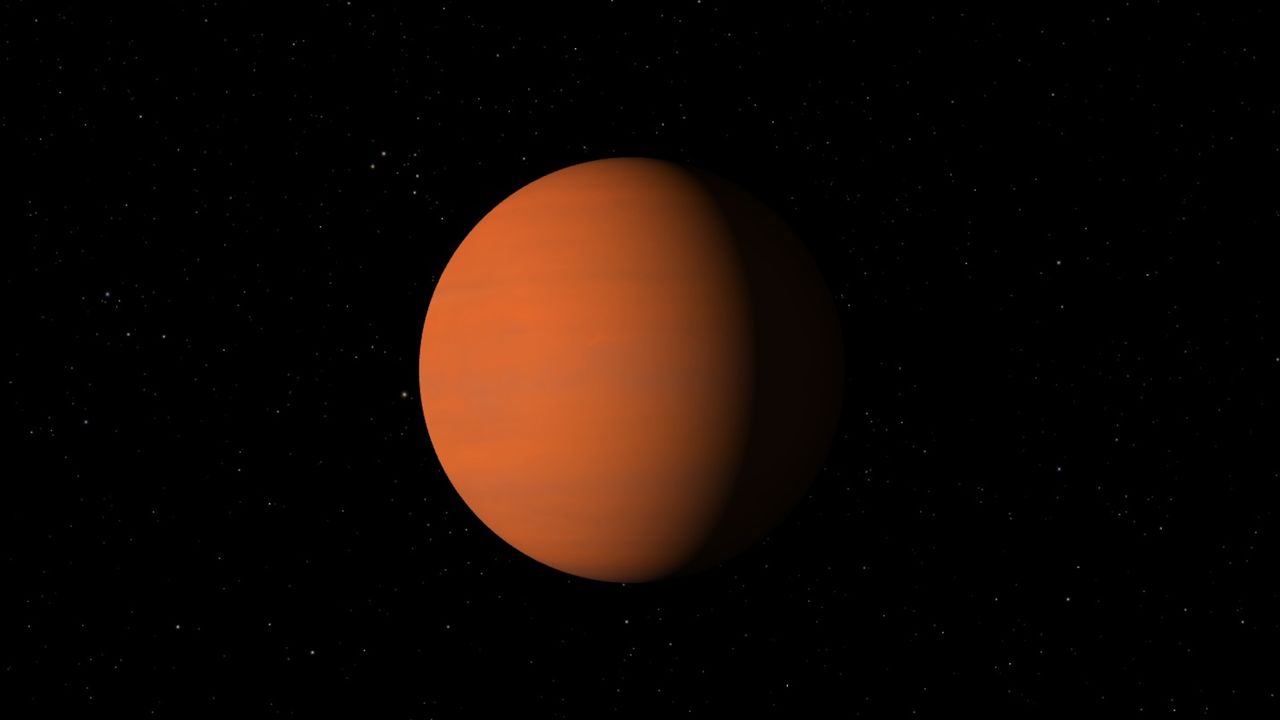

The astronomers utilized spectroscopic analysis to study the star’s light, revealing the presence of a planet they named 51 Pegasi b, or Dimidium. This gas giant, larger than Jupiter yet with half its mass, orbits incredibly close to its star, approximately 5 million miles (about 8 million kilometers) away. Its rapid orbit allows it to complete a revolution every 4.2 days, categorizing it as a “hot Jupiter.”

This discovery was not only a scientific milestone; it opened avenues for further exploration. Following Mayor and Queloz’s findings, researchers quickly confirmed the existence of additional exoplanets, igniting significant interest in the hunt for potentially habitable worlds. By 2004, astronomers at the Lick Observatory in California had captured the first photographic evidence of an exoplanet, leading to a surge in discoveries.

The implications of their work extend beyond mere discovery. For decades, astronomers had sought signs of life beyond Earth. Efforts began as early as the 1960s, focusing on detecting radio signals from intelligent civilizations. By the 1980s, scientists realized they could potentially identify habitable planets by studying the light emitted from their stars. The search for these planets had already seen some false alarms, such as a Canadian team’s misidentified signals in 1987, which were only confirmed in 2003.

In recognition of their groundbreaking work, Mayor and Queloz were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2019, sharing the honor with Canadian physicist James Peebles, who contributed to our understanding of dark energy and matter. Their discovery of Dimidium not only transformed our understanding of planetary systems but also laid the groundwork for the identification of thousands of exoplanets.

As of now, astronomers have confirmed the existence of at least 6,000 exoplanets, ranging from hot Jupiters to super-Earths and water worlds. While none have been confirmed to harbor life, the search continues, with many promising candidates identified.

The work of Mayor and Queloz has inspired a generation of astronomers and has positioned humanity closer to answering the age-old question of whether we are alone in the universe. Each new discovery adds to the rich tapestry of our understanding of the cosmos, and ongoing advancements in technology promise even greater revelations in the years to come.