A recent study reveals that the early universe may contain far fewer tiny galaxies than previously believed. Led by Xuheng Ma from the University of Wisconsin, this research challenges long-standing assumptions about the abundance of these small cosmic structures. The findings, published in a paper available on the preprint database arXiv, suggest significant implications for our understanding of the universe’s evolution.

For years, astronomers have looked back into the cosmos, anticipating a treasure trove of diminutive galaxies hidden in the dark. Conventional wisdom indicated that smaller galaxies should be more numerous. However, Ma and his team propose that many of these galaxies may have vanished due to cosmic conditions during the universe’s formative years.

To investigate the presence of these elusive galaxies, researchers focused on Abell 2744, a massive galaxy cluster known for its significant gravitational lensing effects. This phenomenon bends and magnifies light from distant celestial objects, enabling astronomers to observe galaxies from the early universe, specifically from the Epoch of Reionization, which occurred approximately 12 billion to 13 billion years ago. This era marks a pivotal transformation, as the first stars and galaxies emitted ultraviolet light, ionizing hydrogen gas and clearing the cosmic fog.

Despite expectations, the data revealed an unexpected trend. Traditionally, studies have relied on a luminosity function to chart the number of galaxies at various brightness levels. This function typically indicates that more small, faint galaxies exist than larger ones. However, Ma’s research unveiled a peak in the data, suggesting a decline in the population of the smallest galaxies. This phenomenon, termed “faint-end suppression,” indicates that there are not as many small galaxies as earlier theories predicted.

The study proposes that intense radiation from the universe’s first stars could have heated surrounding gas, preventing low-mass galaxies from retaining the material necessary for star formation. As a result, these galaxies may have remained dim and dark, ultimately becoming “ghosts” of their potential selves.

The validity of these findings hinges on the accuracy of the gravitational lensing model used for Abell 2744. If the map of dark matter in this cluster is flawed, the calculations regarding the missing galaxies could also be inaccurate. Nevertheless, the analysis suggests that the trend of faint-end suppression is genuine and points to a significant gap in our understanding of early cosmic development.

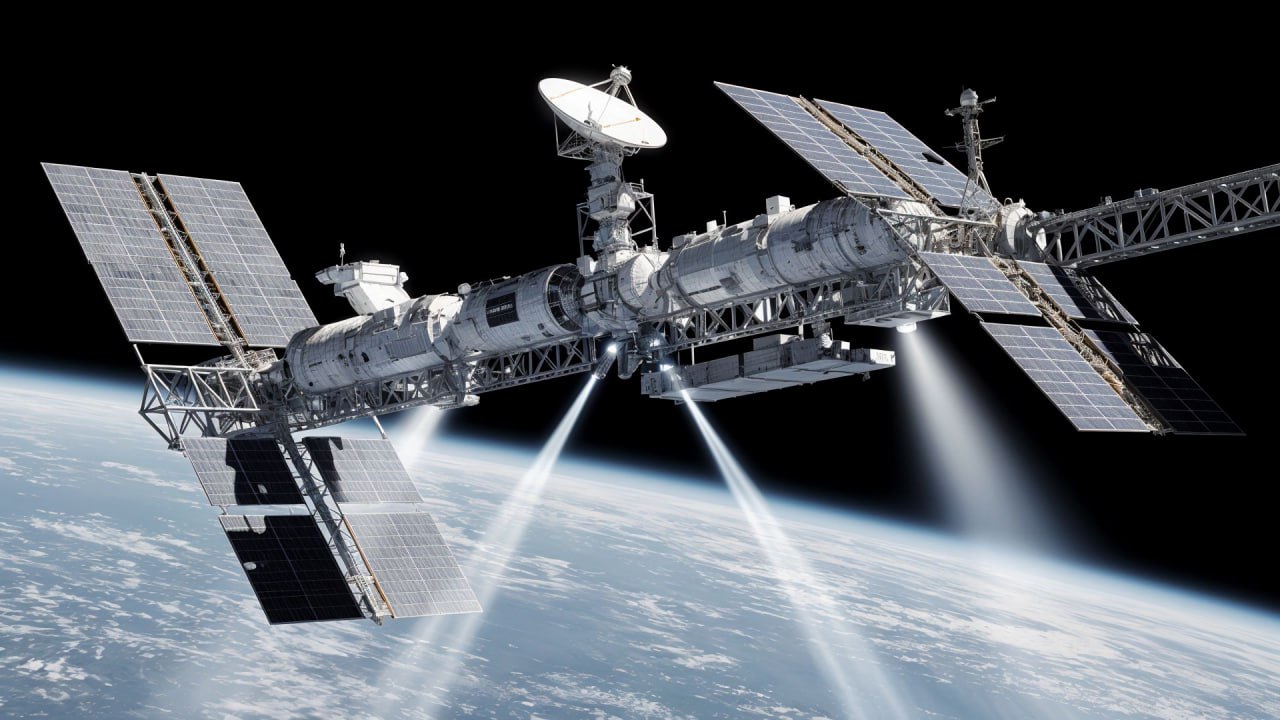

This discovery poses challenges for current models of the Epoch of Reionization. If ultrafaint galaxies are not the primary contributors to this phase, researchers may need to reevaluate the role of slightly larger, more established galaxies in the universe’s evolution. As scientists continue to gather data from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and other upcoming surveys, they aim to determine whether this trend is a localized anomaly or a fundamental characteristic of galactic formation.

In summary, the early universe appears less populated with tiny galaxies than previously thought, inviting further exploration and research into our cosmic history. As astronomers refine their tools and methodologies, they remain hopeful that additional data will shed light on the mysterious beginnings of our universe.